The representativeness of the protected area system is improving with some significant additions to underrepresented areas, but some bioregions and vegetation classes are still underrepresented, particularly in the central and western regions.

There has been little change to the system of marine protected areas over the past three years.

Conservation on both private and public land provides greater connectivity across landscapes and is becoming increasingly important. A range of measures has been developed under the Conservation Partners Program to encourage and support conservation on private land.

Related themes: 15 Invasive species | 18 Wetlands

NSW indicators

| Indicator and status | Environmental trend |

Information availability |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Area of terrestrial reserve system | Decreasing impact | ✔ ✔ ✔ | |

| Area of the marine protected areas system | Stable | ✔ ✔ | |

Notes: Terms and symbols used above are defined in About SoE 2015 at the front of the report.

Context

Protected areas of land and water in original or close to original natural condition are the cornerstone of nature conservation efforts in NSW.

For the terrestrial environment, nearly all of such land is in the state's public reserve system. This is a substantial network of protected areas that:

- conserves representative areas of the full range of habitats and ecosystems, plant and animal species, and significant geological features and landforms in NSW

- protects areas of significant cultural heritage

- provides opportunities for recreation and education.

As well as the protected area system, NSW also conserves the environment through other measures. Conservation of natural values across the whole is increasingly being focused on public and privately owned areas outside the reserve system (for details on the status of wetlands conservation, see Theme 18: Wetlands).

In the NSW marine environment, six marine parks with multiple-use zoning plans conserve marine and coastal ecosystems and habitats, while permitting a wide range of compatible uses. Twelve aquatic reserves are in place along the NSW coast to conserve biological diversity, or particular components of biological diversity as per the new Marine Estate Management Act 2014.

The National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) in the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) is the agency responsible under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NPW Act) for managing and protecting more than seven million hectares of conservation reserves in NSW. These are mostly land-based, but sometimes include estuarine and oceanic areas. OEH also administers several schemes that encourage and support landholders to protect biodiversity on private land.

The recently created Marine Estate Management Authority is responsible under the Marine Estate Management Act for overseeing and coordinating the management of the entire NSW marine estate (all tidal rivers, estuaries, shoreline, and waters out to three nautical miles) as a single continuous system, and is developing a marine estate management strategy to coordinate implementation by all the other agencies involved.

The Department of Primary Industries (DPI Fisheries) undertakes the day-to-day management of NSW marine parks and aquatic reserves, and is responsible under the Fisheries Management Act 1994 for the protection of key fish habitat, both inland and marine.

The Forestry Corporation manages flora reserves under s.16 of the Forestry Act 2012 and Schedule 3 s.6.

Fourteen state parks cover significant natural areas of bush and wetlands, although they are often reserved primarily for nature-based recreation. They are managed by various trusts under the Crown Lands Act 1989.

Other important natural areas are also administered by trusts under the Crown Lands Act, often with day-to-day management by local councils (e.g. Warringah Council manages Manly Warringah War Memorial Park, which comprises several Crown reserves around Manly Dam).

Local land services manages travelling stock routes (TSRs) as a trust under the Crown Lands Act in the central and eastern divisions of NSW, and TSRs in the western division of the state are held by private landholders as leaseholders under the Act.

Status and trends

Land-based formal reserve system

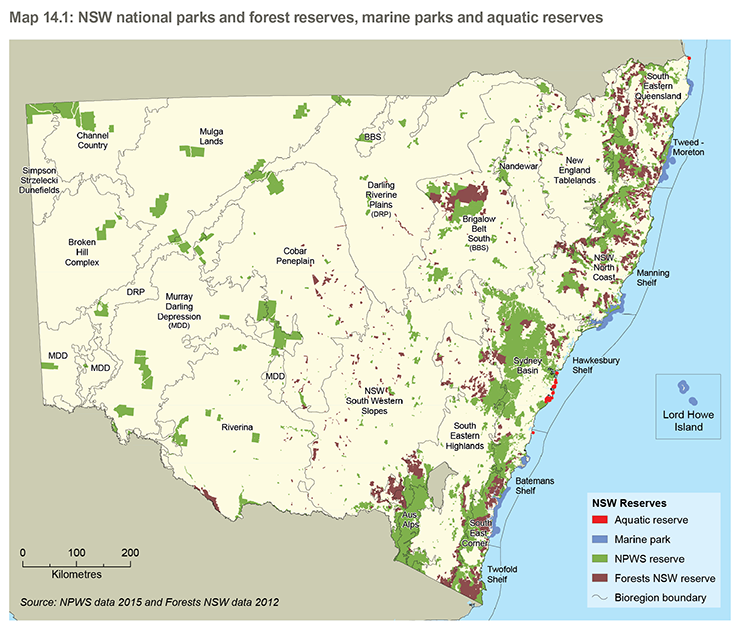

This section focuses on protected areas that meet certain formal reserve levels under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Protected Areas Categories System. These are depicted in Map 14.1. Other types of less formally managed areas that have value for nature conservation are considered in later sections.

Map 14.1: NSW national parks and forest reserves, marine parks and aquatic reserves

At 1 January 2015, the area of the NSW public reserve system reserved under the NPW Act, across 886 parks, was a total of 7,107,533 hectares, or approximately 8.9% of NSW.

An additional 481,417 hectares are reserved for conservation as Crown reserve and flora reserve that covers approximately 0.6% of NSW.

State conservation areas (SCAs) form part of the areas reserved under the NPW Act and provide for dual uses, allowing resource exploration and mining as well as protecting natural and cultural values. A review of SCAs conducted in May 2013 concluded that the dual purpose SCA category was no longer needed for seven SCAs and parts of two SCAs. As a result, 29,424 hectares were reclassified and incorporated into Lachlan Valley National Park.

Further, the former Dharawal SCA was gazetted on 26 March 2013 as Dharawal National Park.

Since 2012, large areas of new parks and reserves have been created. There were 62 additions to parks and reserves ranging up to 29,424 hectares. Table 14.1 summarises the changes in types of terrestrial protected areas in NSW.

The largest areas of parks and reserves created or increased include:

- South Coast (Dharawal National Park)

- Sydney region (Berowra Valley National Park)

- Darling Riverine Plains (Warrambool)

- North Coast (Everlasting Swamp National Park)

- Yathong Nature Reserve (4151 hectares of additional areas added on 1 January 2015).

Table 14.1: Extent and types of terrestrial protected areas in NSW and changes since 2012

| Type of protected area | Total number | Area (ha) | Change since January 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSW national parks and reserves | |||

| National parks | 203 | 5,233,999 | Four new national parks – an increase of 0.9% due to the re-categorisation of state conservation areas and regional parks |

| Nature reserves | 423 | 951,904 | Six new nature reserves – an increase of 1% |

| Aboriginal areas | 19 | 14,198 | No new areas, but a small increase to one existing area |

| Historic sites | 16 | 3,023 | No new sites or increase |

| State conservation areas | 119 | 528,280 | Decrease of 4.7% (five state conservation areas were re-categorised as national parks) |

| Regional parks | 20 | 19,946 | Decrease of 11% (due to re-categorisation of part of regional park to national park) |

| Karst conservation reserves | 4 | 5,228 | No new reserves, but a small increase to one existing area |

| Community conservation areas: Zone 1 | 34 | 132,760 | No new areas, but a small increase to one existing area |

| Community conservation areas: Zone 2 | 5 | 21,661 | No new areas or increase |

| Community conservation areas: Zone 3 | 23 | 196,533 | No new areas, but a small increase to one existing area |

| Total | 866 | 7,107,533 | |

| Wilderness declarations | |||

| Wilderness areas | 51 | 2,099,278 | An increase of 0.4% |

| Wild rivers | 7 rivers and associated tributaries | No new rivers and associated tributaries | |

| Reserved areas in state forests | |||

| State forest dedicated reserve: special protection | Not reported | 29,123 | No change |

| State forest informal reserve: special management | Not reported | 175,431 | No change |

| State forest informal reserve: harvest exclusion | Not reported | 240,349 | No change |

| Total state forests reserves | 444,903 | ||

Source: NPWS data 2015 and Forests NSW data 2015 (up to and including 1 January 2015

Progress on long-term reservation objectives in NSW bioregions

Many regional ecosystems remain poorly reserved. In general, the best-protected ecosystems are those on the steep ranges of eastern NSW, much of the coast, and the Australian Alps. Poorly protected ecosystems include most in far western NSW; the northern, central and southern highlands and western slopes; and those on the richer soils of the coastal lowlands.

There is an ongoing targeted program for new additions in underrepresented areas. SoE 2012 (EPA 2012) reported that less than 2% of the Broken Hill complex was formally reserved. This is no longer the case as all bioregions now have 2% or more area in the reserve system.

Of the 18 bioregions in NSW, four still have fewer than 50% of their regional ecosystems included in the reserve system. At a finer scale, 30 of the 131 subregions in NSW still have fewer than half of their regional ecosystems represented in the reserve system.

Table 14.2 describes progress in meeting the objective of a comprehensive, adequate and representative reserve system across the state.

The NSW National Parks Establishment Plan 2008 (DECC 2008) is currently in the process of being reviewed. Further details are available at OEH priorities in acquiring land.

Table 14.2: Progress towards meeting long-term reservation objectives in NSW bioregions

| NSW section of the bioregion | Area (hectares) | Area in formal reserves managed by NPWS (hectares) | Reserves (% of bioregion) | Remaining native vegetation cover (% of bioregion) | Progress towards comprehensiveness (%)* | Progress towards representativeness (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulga Lands | 6,591,283 | 287,702 | 4.4 | 99 | 59 | 56 |

| Channel Country | 2,340,662 | 218,779 | 9.4 | 100 | 41 | 44 |

| Simpson–Strzelecki Dunefields | 1,095,796 | 119,146 | 10.9 | 100 | 43 | 35 |

| Broken Hill Complex | 3,763,317 | 75,616 | 2.0 | 100 | 38 | 27 |

| Australian Alps | 464,297 | 377,381 | 81.3 | 97 | 100 | 100 |

| Murray–Darling Depression | 7,935,880 | 462,295 | 5.8 | 89 | 70 | 38** |

| South East Corner | 1,153,600 | 496,561 | 43.0 | 85 | 97 | 97 |

| Riverina | 7,022,691 | 237,014 | 3.4 | 50 | 78 | 48 |

| Cobar Peneplain | 7,377,221 | 194,083 | 2.6 | 67 | 50 | 52 |

| NSW North Coast | 3,962,537 | 980,148 | 24.7 | 69 | 92 | 88 |

| Sydney Basin | 3,573,565 | 1,439,968 | 40.3 | 68 | 98 | 91 |

| Darling Riverine Plains | 9,419,258 | 249,877 | 2.7 | 51 | 48 | 45 |

| South Eastern Queensland | 1,647,040 | 227,633 | 13.8 | 53 | 95 | 86 |

| South Eastern Highlands | 4,989,020 | 729,281 | 14.6 | 38 | 85 | 73 |

| New England Tableland | 2,860,297 | 274,325 | 9.6 | 43 | 86 | 72 |

| Brigalow Belt South | 5,624,738 | 487109 | 8.7 | 37 | 65 | 48 |

| Nandewar | 2,074,881 | 85,949 | 4.1 | 39 | 70 | 72 |

| NSW South Western Slopes | 8,103,373 | 183,590 | 2.3 | 13 | 54 | 49 |

Notes: * The national reserve system (NRS) target for comprehensiveness is for at least 80% of extant regional ecosystems in each IBRA bioregion defined in the Interim Bioregionalisation of Australia (IBRA) to be protected in public reserves by 2015. Ecosystems in a bioregion are excluded from the calculation where they lie along the margins of the region and their occurrence is relatively insignificant.

The NRS target for representativeness is for at least 80% of extant regional ecosystems in each IBRA subregion to be protected in public reserves by 2025. Ecosystems in a subregion are excluded from the calculation where they lie along the margins of the region and their occurrence is relatively insignificant.

** Some of the more substantial changes have occurred due to the revised boundaries of IBRA v7. This change in MDD is largely due to the recognition of a third MDD subregion within NSW, extending across the border from SA.

Private land conservation

Private land conservation provides a crucial supplementary role to the public reserve system in NSW. With less than 10% of NSW conserved in national parks and reserves and more than 70% of the state under private ownership or Crown lease, private land conservation is an essential element in conserving the biodiversity of NSW. Around 3.9% of land in NSW currently has some form of private land conservation management (see Table 14.3).

Table 14.3: Private land conservation mechanisms and area protected in NSW

| Conservation mechanisms | Number | Area protected (hectares) |

|---|---|---|

| Conservation agreements | 396 | 146,000 |

| Wildlife refuges | 678 | 1,936,358 |

| Nature Conservation Trust agreements | 91 | 24,886 |

| Incentive property vegetation plans | 1885 | 860,258 |

| Registered property agreements | 336 | 52,606 |

| BioBanking agreements | 32 | 4,845 |

| Land for wildlife | 1125 | 87,242 |

| Indigenous protected areas | 9 | 16,000 |

| Total | 3,128,195 |

Source:

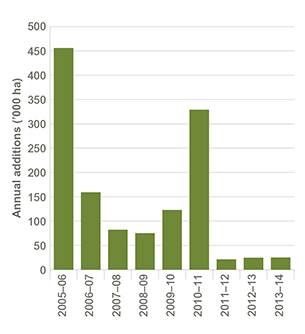

Since SoE 2012, relatively fewer additions have been made to the public reserve system (Figure 14.1) and private conservation initiatives have become increasingly important in a relative sense compared to formal reservation.

Figure 14.1: New formal conservation areas added each financial year beginning from 2005–06

Source: NPWS 2015

Data for Figure 14.1

Conservation on other tenures

Forests NSW conservation zones

Forestry Corporation uses a land classification system in state forests that sets out management intent and identifies areas set aside for conservation.

Through this zoning system, about 486,000 hectares of state forest (22%) are excluded from harvesting for conservation reasons. A further 544,964 hectares are excluded from harvesting for silvicultural reasons. These areas, 47% of the total area of state forests, make a significant contribution to the protected area network in NSW.

Travelling stock routes

Travelling stock routes (TSRs) are authorised thoroughfares for moving stock from one location to another. On a TSR, grass verges are wider and property fences are set back further from the road than usual, providing feeding stops for travelling stock.

TSRs are located on Crown land, and are often found in environments that are poorly represented in the public reserve system, heavily disturbed and in poor condition. The natural values of approximately 700,000 hectares of TSRs in the eastern and central divisions of NSW are currently being assessed.

Marine protected areas

The Marine Estate Management Act 2014 commenced on 19 December 2014 and now provides for the declaration and management of marine parks and aquatic reserves. The Marine Parks Act 1997 and aquatic reserves division of the Fisheries Management Act 1994 have been repealed.

Management rules for marine parks are contained in the Marine Estate Management (Management Rules) Regulation 1999. The Aquatic Reserve Notification 2015 (NSW Government 2015) sets out the activities prohibited within each aquatic reserve.

A new project announced in December 2014, the Hawkesbury Shelf marine bioregion project, will assess marine biodiversity within the Newcastle–Sydney–Shellharbour region. The assessment will include a review of the current management arrangements for the 10 aquatic reserves in this region.

Types of marine protected areas

As reported in SoE 2012, there are three types of marine-protected areas in NSW: marine parks, aquatic reserves and the marine components of national parks and nature reserves.

Extent of marine protected areas

Day-to-day management of marine parks in NSW is the responsibility of the Department of Primary Industries. A slight decrease in sanctuary zones is expected in mid to late 2015 from the NSW Government's decision to rezone 10 sites from 'sanctuary zone' to 'habitat protection zone' to make shore-based recreational line fishing lawful.

Pressures

Threats to values in terrestrial reserves

The values of the NSW reserve system are impacted by both current and emerging threats. Every three years, OEH reports on the state of the parks of NSW. In 2013, the major reported threats to terrestrial reserves were weeds, pest animals, fire, and habitat and species isolation (Table 14.4). Climate change and illegal activities are identified by a large number of park managers as ongoing or emerging threats and these are also profiled in this section.

Table 14.4: Major threats to park values reported in 2013

| Type of threat | Number of parks identifying this threat | Total area of all parks affected |

|---|---|---|

| Weeds | 654 | 28% |

| Pest animals | 567 | 40% |

| Fire | 360 | 29% |

| Habitat / species isolation | 196 | 4% |

Source: NPWS State of the Parks data 2013

The State of the Parks program is based around a triennial online survey that asks park managers to provide current information about each of their parks. The program collects a wide variety of information about all parks in the NSW reserve system.

Weeds

More than 1750 introduced plant species have established self-sustaining populations across NSW, with over 340 recognised as significant environmental weeds. Across the reserve system, some of the most invasive weeds are bitou bush, lantana, blackberry, scotch broom, privet, introduced perennial grasses, and exotic vines, all of which occur to varying degrees of severity. Just under three-quarters of reserves across NSW have identified weeds as a current threat, with 28% of the total area of these reserves affected by this threat. The severity of this impact is considered to be moderate to high across these reserves. This means that the threat will lead to a moderate to major reduction in extent and/or condition of reserve values within three to five years, if it continues to operate at current levels. Reserve values that are most frequently reported as being affected include threatened flora and fauna, endangered ecological communities and Aboriginal sites including rock engravings and grinding grooves.

Pest animals

A number of pest animals, including foxes, wild dogs, pigs, rabbits, goats and feral cats are also widespread across the reserve system and the landscape generally. Feral horses, deer, rats and cane toads present localised issues in some reserves and emerging pest threats include pest birds, such as common mynas, exotic turtles and invertebrate pests like the pandanus planthopper. Pest animals have been identified as a current threat in over half of the reserves, with the total area potentially affected high. This reflects that many pest animals can travel over large distances and accordingly affect a greater proportion of the reserve system. Pest animals pose a significant threat to native wildlife, including threatened species, through competition and predation.

Fire

This is an ongoing threat to the reserve system, though active planning and threat mitigation reduces the severity of impacts and protects life and property.

During 2012–13, there were 351 wildfire incidents, compared to a five-year average of 200 per annum. The total area burnt was approximately 132,500 hectares, compared to the five-year average of 58,403 per annum.

During the last 10 years, 33% of fires in the reserve system were caused by lightning strike, which burnt 59% of the total area affected by fire. Arson or other suspicious causes accounted for 29% of the fires, with this accounting for 9% of the area burnt by wildfires.

Habitat and species isolation

Reserves where habitat and species isolation has been identified as a current threat typically lack connectivity between the reserve system and key habitats and corridors. High levels of urban interface or agricultural lands bounding the perimeter of the reserve represent ongoing challenges in managing this threat.

Illegal activities

Illegal activities are of increasing concern across the reserve system. Activities leading to impacts on values include antisocial behaviour, arson, collection of plants or other materials, collection or release of animals, harming of animals, plants or habitats or approaching marine animals at close distance, illegal commercial operations, vandalism and related offences, vehicle-related offences and other wildlife crimes.

Overall, vehicle-related offences and vandalism affect the largest area of parks. These activities have a negative effect on visitors' experiences. They also affect biodiversity, particularly threatened fauna, flora and endangered ecological communities.

Climate change

This will have an impact on the reserve system due to the increased severity and occurrence of bushfires, increased impacts on coastal reserves from storms and sea level rise, along with increased weed invasion and loss of specialised habitats, for example, in sub-alpine areas. Some of the reserve values affected or potentially lost include threatened seabird habitat, freshwater lagoons, saltmarsh areas, frontal dune systems, and rainforest species, resulting in changes to species distribution and abundance.

Threats to conservation on private land

The pressures that affect protected areas on private land are similar to those affecting public reserves. These include weeds and pest animals, fire, habitat isolation, illegal activities including clearing of native vegetation, and the impacts of stock encroachment, and neighbouring land uses.

Where the primary land use is a form of agricultural production, some activities may not be completely compatible with specific conservation objectives. Land managers may need to address potential threats from land uses that are not compatible with conservation values. Unpredictable events, such as bushfires or sustained drought, may exacerbate these impacts.

Monitoring and support services can assist private landholders to manage their land for long-term conservation and sustainable production. NSW Government support includes providing extension and information services, incentive programs and facilitating state or federal tax concessions.

Threats to marine protected areas

The key threats to marine protected areas include overuse of resources, invasive species, marine pollution, land-based impacts and climate change (MBDWG 2008).

Community opinion on threats to marine protection

In 2014, the NSW Government surveyed the community to determine their views on the values, benefits, threats and potential opportunities that they derive from the marine estate.

Results revealed that the community identified pollution in its different forms as the greatest threat to environmental values and benefits, such as littering, sediment and runoff, and oil and chemical spills.

The community perceived the top economic threats to the marine estate as water pollution affecting tourism, loss of natural areas and habitats affecting tourism, and increasing costs to access the marine estate.

The top social threats to negatively impact the marine estate are antisocial behaviour, loss of appeal due to water pollution, littering and overcrowding.

Responses

Additions to the land-based formal reserve system

Since January 2012, 66 additions were made to the reserve system across 13 NSW bioregions, including Brigalow Belt South, Cobar Peneplain, Darling Riverine Plains, Murray–Darling Depression, Nandewar, New England Tablelands, NSW North Coast, NSW South Western Slopes, Riverina, South East Corner, South Eastern Highlands, South Eastern Queensland and Sydney Basin.

These additions provide improvements to the connectivity of existing reserves, as well as improvements to biodiversity protection.

There were 29 additions to parks in the Great Eastern Ranges, which provide significant habitat corridors across NSW. There were significant wetland additions on the Clarence River Floodplain (Everlasting Swamp, a large coastal floodplain wetland of national and international significance) and in the Gwydir wetlands.

Private land conservation

In 2014 the Minister for the Environment established an independent review panel to review the Native Vegetation Act 2003, Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, Nature Conservation Trust Act 2001 and parts of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974. The aims of the review were to recommend simpler, more streamlined and effective legislation. The panel provided 43 recommendations in its report (Byron et al. 2014) including a number of recommendations concerning private land conservation.

The panel recommended the consolidation of private land conservation into a three tiered system including a biodiversity offsetting mechanism, voluntary conservation agreements, and wildlife refuges. It also recommended the government consider additional investment in positive conservation action.

Plans of management for the formal land-based reserve system

At 1 January 2015, a total of 368 plans of management (PoMs) have been adopted, covering 547 parks and reserves. In total, more than 5.9 million hectares are now covered by a plan of management, representing around 80% of the reserve system. Those parks which do not yet have a PoM have a statement of management intent (SMI). An SMI is an interim document outlining the management principles and priorities for an individual park with reference to its key values and major threats.

Management directions are included in each SMI with reference to the diversity of existing thematic plans that may already be in place for that park, for example, a fire management strategy. Publication of a draft plan of management will replace these statements of management intent.

Managing threats in the land-based reserve system

Weed and pest management

The NSW Government works across agencies to ensure successful weed and pest management on public tenures.

Priorities include managing key threatening processes, including those caused by weeds. NPWS is making significant progress in the control of major environmental weeds. For example, through its Bitou Bush Threat Abatement Plan (DEC 2006), the NSW Government has reduced the spread of bitou bush and greatly reduced its density in national parks. Survey results at over 30 sites show that where control and adequate monitoring has occurred there has been recovery of native biodiversity.

In NSW, pest management priorities for the conservation of biodiversity are focused on threatened species, and are identified in the Threatened Species Priorities Action Statement (PAS) and in individual threat abatement plans (TAPs). These documents set priorities for pest management on parks with a focus on protecting threatened species. (See also Theme 15: Invasive species.)

The PAS and TAPs inform the regional pest management strategies which detail priorities across the state. These were developed with extensive stakeholder consultation, to help coordinate on-park pest management programs with pest management on surrounding lands.

The NSW Government works closely with stakeholders including the local land services and private land managers to tackle wild dog problems across the state under a national wild dog action plan.

Fire management

Managing fire is a core function of NPWS, with the overriding objective being to safeguard human life and property. NPWS undertakes the majority of all hazard reduction across the state. Consultation is undertaken with local communities, bushfire management committees, rural fire brigades and other interested parties in the preparation of fire management plans and strategies. One hundred per cent of the NSW reserve system is covered by a reserve fire management strategy (RFMS), except newly gazetted areas. Draft RFMS are developed for new reserves within three months of being gazetted.

Under the Enhanced Bushfire Management Program, the NSW Government has committed to nearly double hazard reduction and improvement of bushfire response capabilities on parks and reserves by 2016. An additional $62.5 million over five years from 2011 has been allocated to NPWS for hazard reduction and an additional 94 trained fire fighters have been employed full time. In the three years to June 2014, NPWS worked with the Rural Fire Service to carry out hazard reduction burn operations covering over 360,000 hectares. The average annual area treated, approximately 120,000 hectares, was nearly double the average for the previous three-year period.

In 2013, NPWS released Living with Fire in NSW National Parks – a strategy for managing bushfires in national parks and reserves 2012–21 (OEH 2012).

Climate change

NPWS contributes to research to better understand the impacts of projected climate changes on sensitive ecosystems. The Climate Change Impacts & Adaptation Knowledge Strategy 2013–17 (OEH 2013) is addressing information about the impacts and adaptation of climate change. It is one of six themes under the OEH Knowledge Strategy 2013–17.

Marine parks

The NSW Government announced its response to the Report of the Independent Scientific Audit of Marine Parks in NSW (Beeton et al. 2012) in March 2013.

The new approach to the management of the marine estate including marine parks and aquatic reserves is underpinned by the Marine Estate Management Act 2014 that commenced in December 2014 and repealed the former Marine Parks Act 1997.

The new Act provides for the integrated declaration and management of a comprehensive system of marine parks and aquatic reserves in the context of the whole marine estate. It also establishes the Marine Estate Management Authority and an independent marine estate expert knowledge panel.

The Authority has been tasked with implementing a schedule of works during 2015–16 with several tasks of relevance to marine protected areas, including:

- the NSW Marine Estate Management Strategy

- progressing regulations to complement the Marine Estate Management Act, including provisions related to the management of marine parks and aquatic reserves

- a review of marine park zone types, objectives and guidelines for use

- piloting the new approach to marine park management and zoning at Batemans and Solitary Islands marine parks

- overseeing an assessment of the Hawkesbury Shelf marine bioregion to provide advice on options to enhance the conservation of marine biodiversity

- developing a threat and risk assessment framework to identify and assess the key threats and associated risks to the values of the NSW marine estate to inform management of marine parks and aquatic reserves.

Future opportunities

The NSW Government has identified five reserve system planning regions across NSW that group together bioregions at similar stages of reserve building (OEH 2014). The regions will help focus attention on the work required across the state to direct conservation efforts and to develop comprehensive, adequate and representative systems of reserves.

References

Beeton, RJS, Buxton, CD, Cutbush, GC, Fairweather, PG, Johnston, EL & Ryan, R 2012, Report of the Independent Scientific Audit of Marine Parks in New South Wales, NSW Department of Primary Industries and Office of Environment and Heritage, NSW [www.marineparksaudit.nsw.gov.au/audit-report] Cited in: Ch 14

Byron, N, Craik, W, Keniry, J & Possingham, H 2014, A review of biodiversity legislation in NSW: Final Report, Independent Biodiversity Legislation Review Panel, Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney [www.environment.nsw.gov.au/biodiversitylegislation/review.htm] Cited in: Ch 14; Ch 12(1); Ch 12(2); Ch 12(3); Ch 12(4); Ch 12(5); Ch 12(6); Ch 12(7); Ch 12(8); Ch 12(9)

DEC 2006, Bitou Bush Threat Abatement Plan, Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW), Sydney [www.environment.nsw.gov.au/bitoutap] Cited in: Ch 14

DECC 2008, New South Wales National Parks Establishment Plan 2008, Directions for building a diverse and resilient system of parks and reserves under the National Parks and Wildlife Act, Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW, Sydney [www.environment.nsw.gov.au/acquiringland/WhatAreOurPrioritiesInAcquiringLand.htm] Cited in: Ch 14

EPA 2012, New South Wales State of the Environment 2012, NSW Environment Protection Authority, Sydney [www.epa.nsw.gov.au/soe/soe2012] Cited in: Ch 14; Ch 2; Ch 7; Ch 8; Ch 12(1); Ch 12(2); Ch 13(1); Ch 13(2); Ch 16; Ch 17; Ch 19; Ch 20(1); Ch 20(2)

MBDWG 2008, A National Approach to Addressing Marine Biodiversity Decline, report to the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council by the Marine Biodiversity Decline Working Group, Canberra [www.environment.gov.au/resource/national-approach-addressing-marine-biodiversity-decline-report-natural-resource-management] Cited in: Ch 14

NSW Government 2015, 'Aquatic Reserve Notification 2015 under the Marine Estate Management Act 2014', NSW Government Gazette, no. 32, 17 April 2015, pp. 989–92 [www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/epub?bulletin=20150419#Gazette_2015-32] Cited in: Ch 14

OEH 2012, Living with Fire in NSW National Parks – a strategy for managing bushfires in national parks and reserves 2012–2021, Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney [www.environment.nsw.gov.au/fire/120690livfire.htm] Cited in: Ch 14

OEH 2013, Climate Change Impacts & Adaptation – Knowledge Strategy 2013–17, Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney [www.environment.nsw.gov.au/knowledgestrategy/ClimateChange.htm] Cited in: Ch 14